The police's first public acknowledgment of “signs of interference” in the disappearance of two people in the Gulf of Mexico marked a critical turning point in the overall understanding of the case. From being described as a tragic maritime incident, the story now had to move into a more dangerous gray area, where familiar assumptions were no longer sufficient to reassure the public. When the investigating authorities confirmed that what happened might not have been purely a natural phenomenon, the entire case file had to be reread from scratch.

For weeks prior, public opinion had been guided by a relatively simple scenario: adverse weather conditions, human error, and the inherent risks of the marine environment. These were the causes cited in dozens of similar disappearances over the decades. But it was precisely this repetition that made the police's new statement so shocking. If this was no longer a random accident, then what really happened in the final hours before the ship lost contact?

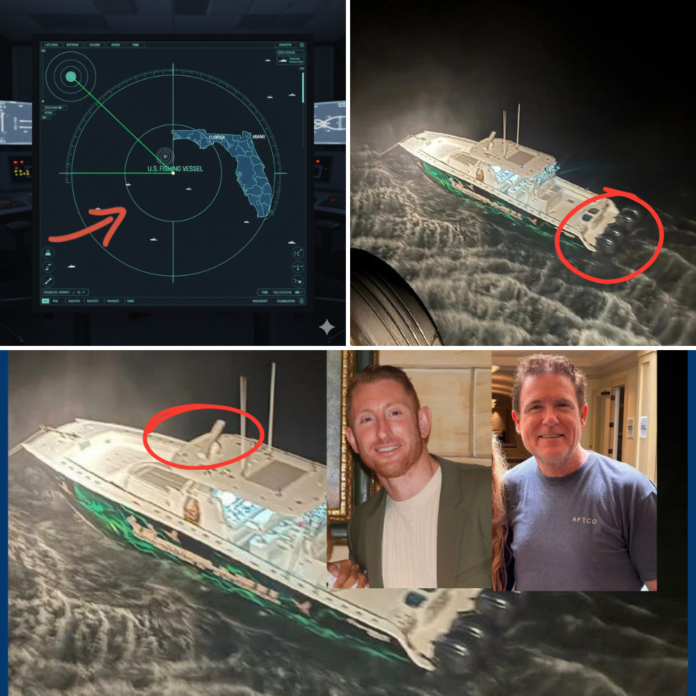

According to investigative sources, the newly emerged detail is not direct evidence, but rather a series of technical anomalies and behavioral disturbances that cannot be explained by normal natural scenarios. The anomalies lie in the sequence, the timing, and the way the ship's systems reacted—or failed to react—to the supposed emergency. These elements, when considered separately, might be overlooked. But when placed together, they constitute a question of sufficient weight to force the police to change their official wording.

Notably, this is the first time in the investigation that the concept of “interference” has been publicly introduced, albeit cautiously. This caution does not diminish the seriousness of the statement; on the contrary, it shows that investigators are facing a far more complex possibility than they had anticipated. In a legal context, acknowledging the possibility of interference means that the incident can no longer be viewed as a random, unintentional event.

The disappearance of the two people in the Gulf of Mexico therefore falls outside the realm of typical maritime accidents. It begins to take on the characteristics of an event with an active element, where human behavior—whether direct or indirect—may have played a decisive role. This raises concerns that there may have been stages in the initial investigation where crucial hypotheses were not fully considered, or were relegated to safer conclusions.

Maritime experts have warned that, in many previous cases, prematurely attributing the cause to natural causes can lead to the omission of crucial evidence. When a ship loses contact, the system's instinct is to seek the least disruptive explanation. However, this incident shows that this approach may no longer be appropriate in an age where technical data and electronic traces are increasingly central to establishing the truth.

The detail that has particularly drawn public attention is the alleged interference **before** the cruise ship lost contact. This completely overturns the initially published sequence of events. If the interference occurred beforehand, then the loss of contact was not the beginning of the tragedy, but merely the final consequence of a series of actions that had been silently unfolding. This is precisely what makes the “natural accident” hypothesis so difficult to sustain.

In typical maritime accidents, technical malfunctions or severe weather are usually the direct causes of loss of control and communication. But when there are indications that the system was deliberately tampered with, the question is no longer “what happened,” but “who did it, and for what purpose.” This is a question that investigators have yet to answer publicly, but its very existence is enough to shift the entire focus of the case.

The police admission also raises another concern: whether crucial information was overlooked or not released during the early stages of the investigation. In complex cases, delaying or concealing information—whether for professional reasons or public pressure—can severely damage public trust. And when that trust is eroded, any subsequent conclusions will be subject to skepticism.

The families of the victims, meanwhile, have long expressed skepticism about the accident conclusion. The police statement, while not providing a definitive answer, inadvertently confirms that those suspicions were not entirely unfounded. When the possibility of intervention is raised, the story is no longer an inevitable tragedy, but an incident that could have been prevented if the evidence had been clear.

The initial findings are being taken more seriously.

On a broader level, the Gulf of Mexico incident raises worrying questions about maritime security and the actual level of oversight of cruise ships. If interference can go undetected, the loophole isn't limited to a single vessel, but could exist throughout the entire system. This is a problem that goes far beyond a single case, touching upon the responsibilities of regulatory agencies and existing safety standards.

Observers suggest that the police's admission of signs of interference may be a result of increasing pressure from data and public opinion. In an age where every signal and every operation leaves a trace, denying or ignoring anomalies is becoming increasingly difficult. And when data begins to contradict the official narrative, the system is forced to adjust, even if that adjustment may have unforeseen consequences.

It's worth noting that, to date, police have avoided using conclusive terms like “crime” or “criminal conduct.” This reluctance reflects the fine line between acknowledging suspicion and asserting the truth. However, the very existence of suspicion is enough to prevent the case from returning to its original state. Once the possibility of intervention is raised, all other hypotheses must be re-evaluated in a new light.

The disappearance of the two people in the Gulf of Mexico is therefore becoming a test of the transparency and integrity of the investigative system. The public no longer accepts simplistic conclusions for complex events. They demand a comprehensive answer, based on data, logic, and accountability. And if that answer is not provided, suspicion will continue to spread, beyond the scope of the specific case.

Historically, many cases are only understood for what they truly are years after the case has been closed. Buried truths, when unearthed, often come at a great cost—not only for the victims, but also for the credibility of institutions that claimed to have done their part. The Gulf of Mexico incident risks becoming another example if the investigation is not pursued to its conclusion.

The admission of signs of interference, therefore, is not just a new detail. It is a warning that this story is far more complex than initially known to the public. And until all questions are answered convincingly, the disappearance of the two people in the Gulf of Mexico will continue to be a worrying crack in the maritime safety landscape—where the line between accident and concealed truth is more fragile than ever.